Where the people can sing, the poet can live — and it is worth saying it the other way around, too: where the poet can sing, the people can live.

James Baldwin

James Baldwin opens the 1964 essay “Nothing Personal” with the hit-parade of available distractions from his adventures channel-flipping. His list begins with women washing their hair and the “gleaming grill-works of automobiles,” then switches to “breasts firmly, chillingly encased” and “teeth forbidden to decay by mysterious chemical formulas.” Today I could generate an equally soul crushing list of distractions from Netflix, Twitter, and Facebook. I am drowning in clever clickbait and advertisements enhanced by masters of increasingly persuasive technology. I can’t unsubscribe faster than the rodents of tech can burrow and gnaw they way into my inbox. I’m up to my eyeballs in spam. I am the tiny boat Hokusi carved in the shadow of a rogue wave, a wave so beautiful and mesmerizing that it’s reproduced more than any other Japanese woodcut. Looking at the wave, it’s easy to miss the tiny wood boat in the wave’s shadow, about to be crushed. That tiny vessel is my soul, a soul I am hellbent on saving, karate-chop by karate-chop, from the increasingly addictive distractions of the our hellacious attention economy. U-N-S-U-B-S-C-R-I-B-E! Take that mother-hubbards! And that! And that!

In the nearly sixty years since Baldwin’s essay, advertising has not relinquished its hold on the consumerist imagination. It still holds out the promise of happiness, just around the corner from the next purchase. Advertisements are everywhere, from the zippers on skinny jeans to gas station pumps with their simpering ads for donuts and energy drinks and touch-less carwashes. Amazon trucks dart through neighborhoods around the clock delivering brown boxes that will never satisfy our addicted consumerist souls. Every sports stadium and museum and even our olympic athletes have corporate sponsors. The pumps at the corner gas stations have those little people inside the screens spewing deals from soda pop to car washes.

I wish to report that I managed to escape the consumerist frenzy that has swelled, crested and crashed with the COVID-19 pandemic. I wish to report that I am not up to my eyeballs in stuff. Book stuff, art stuff, food stuff, house stuff. I wish to report I don’t have a damned Vitamix blender that is collecting dust. If it lives up to the promise of its advertisement, I will be able to pass it down for generations. I wish to report that I was not swayed by the friend who raved about hers and that I was not convinced by her promise that it would revolutionize my relationship with smoothies. Despite its power to crush ice cubes the size of fists and whirr at speeds to make hot soup in minutes, I report my fascination has been short lived. The blender currently rests in the cramped storage cubby under my cooktop, which at times begs for its own replacement with something polished, shiny, and new. Despite the fading patina and dents and specks of rust, the burners still erupt with sapphire flames. When the impulse strikes I reinforce my frail consumerist sobriety with a peek at the dust-covered Vitamix.

Our entire economy and way of life is based on luxuries that we don’t need. In The School of Life, Alain de Botton traces the consumer revolution and the ensuing nearly 400 year debate over pursuing virtue over wealth back to a London physician, Bernard Mandeville, who proposed that what made countries rich was “to ensure demand for absurd and unnecessary things,” an anthem subsequently picked up by David Hume in the essay “Of Luxury” (1752). The modern day version of this argument bobs on the surface of economic debates between free market capitalists and environmentalists.

Is there a way through this economic debate deadlock that has devastated the environment and is returning islands to the sea and their inhabitants searching for new inland communities ten years ahead of schedule, according to this week’s Science News? De Botton proposes we rethink what is possible. Could our species redirect the economic engine we’ve built over the last 400 years to meet higher human needs, those at the top of Abraham Maslow’s 1943 pyramid of human motivation rather than those at the bottom?

To trace the future of capitalism, we have only to think of all our needs that currently lie outside commerce. We need help in forming cohesive, interesting, benevolent communities. We need help in bringing up children. We need help in calming down at key moments (the aggregate cost of our high anxiety and rage is appalling). We need immense help in discovering our real talents (creativity?) in the workplace and in understanding where we can best deploy them. We have aesthetic desires that can’t seem to get satisfied at scale, especially in relation to housing. Our higher needs are not trivial or minor, insignificant things we could easily survive without. They are, in many ways, central to our lives. We have simply accepted, without adequate protest, that there is nothing business can do to address them, when in fact, being able to structure business around these needs would be the commercial equivalent of the discovery of steam power or the invention of the electric light bulb.

Alain de Botton in The School of Life: An Emotional Education

What if consumer capitalism got ambitious about delivering higher sorts of satisfaction and flourishing, such as fostering adult emotional intelligence and creativity?

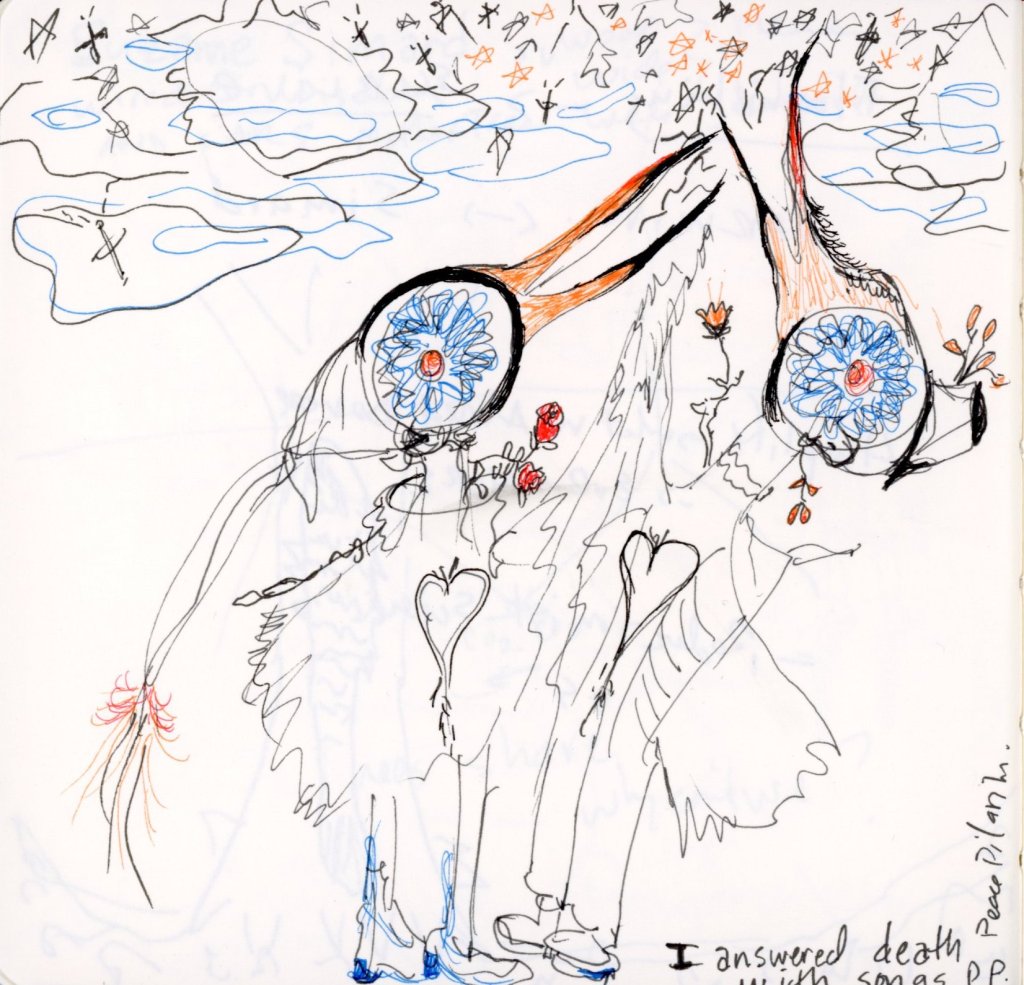

Where shall we begin? I stand with Baldwin “singing for joy, for the hell of it.”